Fifteen years ago, I interviewed my LA-based cousin, Susi Kaminski Klein, about her experiences as a child survivor of the Holocaust. Over the course of four days, hanging out here on Lopez Island and visiting beautiful Victoria, BC, I recorded Susi narrating her story.

Nine years ago, I blogged about Susi’s story as depicted in Jewish Journal of 2016. You can read that here.

Five years ago, with some urging, and a TON of formatting, research and illustration help from my cousin Helen (Susi’s daughter), we turned those notes into a book.

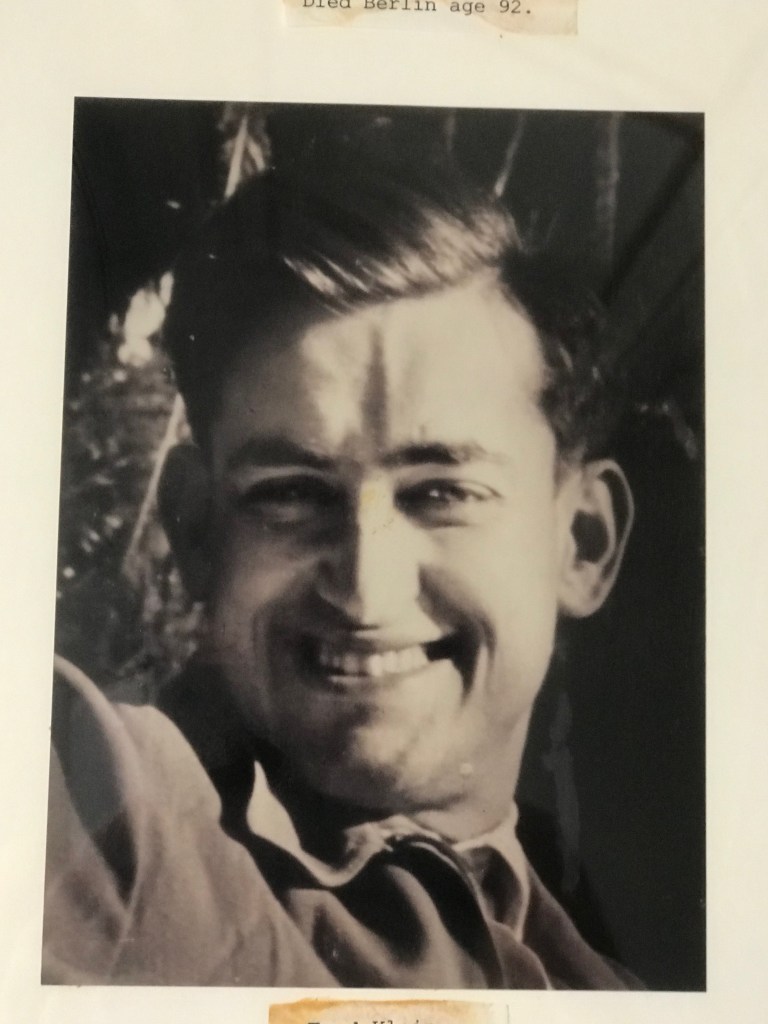

But the lede I’m burying here is this: COUSIN HELEN WAS WAYYYY AHEAD OF ME! In 2011, four years earlier, she had already published the story of her father, Fred Klein. Here it is:

Something you have to understand: back then, self-publishing was HARD WORK. I’ll get to that part in a moment.

What I wanted to know was how Helen’s experience interviewing her father compared to mine, interviewing her mother, and…well, I’ll let Helen tell it. Cuz?

“This will be a short and possibly unexpected answer. I never interviewed my father to capture his story. My father started writing his book, believe it or not in 1997! He went through a number of iterations. During the process he found several people who were willing to edit his work and give him ideas on organization, grammar, etc. I was not involved in that process at all.”

Well, that tracks. Susi had separated and Fred by the time we met, so I never got to meet Fred. From what I’ve learned, I think he must have been an impressive man. Maybe daunting to interview? Not really, Helen said, but…

“I think I would have found it extremely challenging to interview my father. Not because he would not be willing but it is such a vast subject, I would really have had to figure out where to begin, how to organize and structure the questions etc. so honestly I am grateful my father wrote his story on his own and got some guidance from others on organization and structure.”

Keep in mind, my cousin’s working full-time during this entire period. When I interviewed Susi, I had just left my teaching job, so I had the time I needed to organize her story after capturing it on tape.

Also…as Fred Klein’s book cover intimates: he survived Auschwitz. While Susi’s story was horrific and traumatic, including her father being sent to the concentration camp Theresienstadt…it did not involve Auschwitz.

Full disclosure, I’m only partway through No Name, No Number, which is written as a mix of personal account and history lesson. History, I think, is more and more necessary these days when precious little Holocaust history is taught. But personal stories are the most poignant.

Here’s an excerpt from Ch. 7, where, in 1941, still living “freely” in Prague, teenage Fred is forced to labor on a collective farm. I have bolded sentences that especially capture the personal reality of the horror.

“For me, the worst part about the camp was the strenuous physical effort required. I was in extremely bad shape, not accustomed to the job, never having learned to push myself. Sometimes the grueling twelve-hour workday seemed like hell to me. I thought I would never last through them. I had to shovel some three hundred times earth up to a little metal wagon. Sometimes I had to carry very long tree-trunks with a fellow forced laborer. Most of my fellow inmates were in better shape than me and enjoyed teasing me. They had me carry the thick end of the tree-trunks which was so heavy that I almost collapsed, whereas the other fellow had it easy. Had I been in better shape, the work would have been exhausting, but tolerable.”

Here’s another excerpt, from Ch. 11, where in 1944, 22 year-old Fred is unloaded at the dreaded camp. Notice the detail in the middle of the passage:

“I jumped out of the cattle car. Barracks, barracks, barbed wire, gleaming lights. SS men with police dogs, wielding whips. Pajama-clad figures – kapos – and other prisoners, something I had never seen before. This place was cold, frightening, there was nothing soft to humanize it. I stared briefly at the hellish scene, and then I took off my glasses. Shouting and shoving, the kapos and prisoners herded us into rows five men deep and made us stand still. The dogs of the SS were poised to attack us. Somehow the pajama-clad prisoners got us moving forward in a single file.”

“I took off my glasses.” To me that act says, I will not look at this. I will get through it.

So, Helen– your dad wrote out his own book. Why was it not published right away?

“What I can tell you is that my father tried very, very hard to get his book published. He wrote lots of letters to a variety of publishers, but none of them seemed interested. I don’t even know if he ever got answers.”

It’s painful to reflect on this answer. There are so many Holocaust stories. The simple truth– that the sheer quantity of such traumatic stories affects their “marketability”–hurts my stomach.

Helen finishes:

“He finally gave up looking for a publisher, and sadly resorted to literally going to Kinkos, making copies of his book, getting the books comb-bound, and then trying to distribute his book that way.”

Ouch. But then here comes my cousin, to ease her father’s pathway:

“Originally, I published my father’s book in 2007 using Blurb.com. That process was long and tedious, but I pushed through it as I really, really wanted to get it done while my father was alive. Little did I know back in 2007, when I completed the publishing on Blurb, that my father would live to 100, something I am ever so grateful for!”

Which brings us back to this moment. Blurb.com no longer exists. Fred Klein passed away in 2022 (at the age of 100, as Helen said). But thanks to his daughter, Fred’s story lives on…easily available on Kindle! Click here to download and read No Name, No Number, for free.

I would like to thank my cousin Helen for her perseverance (not to mention all the photos!)…and my cousin Susi for hers. They are both role models for me.

And, in this season of deepest darkness, please say an extra prayer for the Fred Kleins of the world. May their stories find resonance.

May their stories become, some day…rare.