One year ago, I was soaking up the sights and sounds of Culver City on my daily walks to the campus of Antioch University for the first residency of my MFA program in Creative Writing. Mostly I was dazzled by the Southern CA flowers.

What I should have used as a photo was a full-blast firehose, because that’s what Residency #1 was like. Back home, I likened my new venture to a switch from hiking to rock-climbing. Not long after, I chose to step away from blogging altogether, devoting all my precious writing time to my most precious writing. Residency #2, last December, received no analysis.

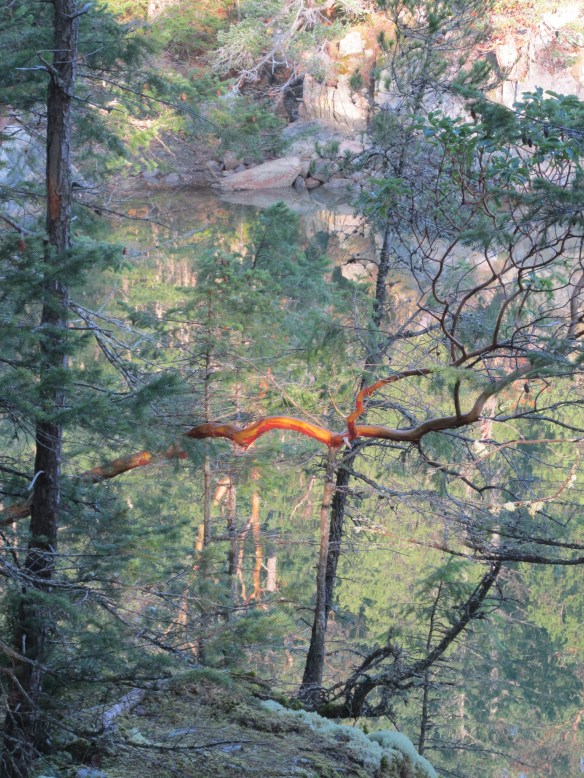

But this summer, riding along that same bike path, I was stopped by a new metaphor: this rainbow tangle of flora:

You gardeners will spot pink and red oleaner, scarlet bouganvillea, orange trumpet vine and blue morning glory, all rampaging joyously over a substrate of purple jacaranda. What I see? A message to stay focused on more stories than mine.

YES, I am writing a novel. YES, it requires my time. But not so much to keep me from this blog’s renewed mission to AMPLIFY voices for justice and understanding. Which is why it felt so perfect, on the same day I took that picture, that I turned on a car radio and discovered House/Full of Blackwomen.

CreativeCapital.org describes the group this way:

House/Full of Blackwomen is conjure art, the insistence movement, activated in store fronts, streets, houses, warehouses, museums, galleries and theaters of Oakland, California. House/Full began as a two-year project and morphed into an eight-year process of 15 public “episodes” which unexpectedly appeared as street processions, all night song circles, secret rituals of Black women resting and dreaming, sacred ceremonies on the track, and multi-media offerings. Black women gathered around a dining room table to recall, rage, rally and restore themselves, while creating ritual performance strategies towards shifting systemic evictions, displacements, erasure and the sex trafficking of Black women and girls: all driven by the core question, “How can we, as Black women and girls, find space to breathe, and be well in a stable home?”

As I listened to Episode One of The Kitchen Sisters’ podcast on NPR, which describes the group’s mission, I was filled with excitement, hope, awe, empathy…and the immediate desire to share all those feelings.

So here you go! The above description, not to mention the podcast itself, says more than I could about the power of this group of 34 women. All I want to do is steer you toward them. Creative Capital says,

The final episode of HouseFull, Episode 15: this too shall pass will premiere March 4–12, 2023. Performance times, venues and details can be found here. All events are sold out, but you can sign up for the mailing list to learn about future performances and project iterations.

And me? I still have a few more days in LA. I still plan to drink from that hose–a little more carefully now, sipping the drips, letting them soak in. Or, to go back to florals, I plan to gather some individual roses as they offer themselves…

…be they writing advice or part of the more tangled, brilliant stories around me. Please join me in discovering House/Full of Blackwomen!